This article may be triggering for some readers.

There is a sense, meeting Lindy Chamberlain-Creighton for the first time, of stepping into history. She was the central character in a real-life courtroom drama that defined us as a nation – and not in a positive way. There’s something still uncomfortable, disturbing, almost primeval about the way Australia rushed to judge her, to think the worst, to invent a fearful maternal stereotype worthy of Greek myth in the face of a simple, heartbreaking loss.

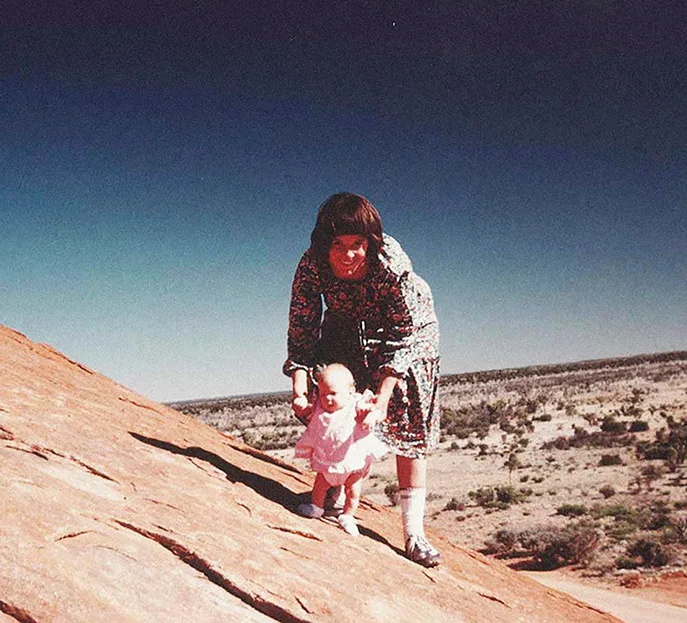

It took almost 32 years for our courts to admit that they were wrong, and that yes, on August 17, 1980, at Uluru, a dingo killed her baby.

Then Lindy appears on a sunny patio with that welcoming smile and history dissolves… If you’re wondering what has happened to Lindy Chamberlain, she is quite simply a grandmother; a delightful, chatty, ordinary woman meeting The Weekly team on a warm Queensland afternoon.

Lindy has agreed to speak with us today about a subject which is of increasing concern to her. “For years,” she says, “I’ve had something on my mind that needs fixing, needs comment. But it’s like our final inquest – we had to wait until there were new people who weren’t biased, who didn’t have preconceived opinions; we had to wait until there was a new coroner – and then we could go back to court without prejudice.

“There are times when you’ve just got to wait until all the ducks are in a row. Kathleen Folbigg’s case has made me think that perhaps the public is now ready to listen to what I have to say.”

Kathleen Folbigg was convicted in 2003, on largely circumstantial evidence, of killing her four children. She was pardoned in June this year, after 20 years in prison, when new scientific research suggested that her children, who shared rare gene mutations, could have died of natural causes.

The Australian Academy of Science commented that the case reflected a need for reform to the legal system to make it more “science sensitive”.

And that is precisely what Lindy is advocating, too.

Why was Lindy Chamberlain convicted?

A great many things went awry in the case against Lindy and her then husband Michael Chamberlain, but perhaps the worst of it was the forensic evidence. The Crown’s forensic scientist, Joy Kuhl, mistook sound deadener in their car (overspray beneath the dashboard during the manufacturing process) for foetal blood, which was taken as evidence that Lindy had killed her nine-week old baby, Azaria, there.

The forensics expert for the defence argued that Kuhl’s methods were flawed. But the jury – with no background in blood science – couldn’t know where the truth lay.

“Later,” Lindy recalls, “a juror told me that, quite frankly, they didn’t understand a word of it. But that Joy Kuhl had a nice manner and looked at them and smiled. She treated them like school children. Whereas the defence guy used all these big, jaw-breaking words and had a manner that they didn’t understand at all.”

There were other errors too. “In the testing,” Lindy says, “the difference between copper and blood is a matter of seconds. An experienced operator would know. She didn’t know the difference. So, she kept getting reactions off everything in our car because we lived in Mount Isa.”

The town is the second largest copper ore producer in Australia. “If you go there today and do that presumptive test for blood, you can get it on every motel room door, every car.”

The jurors were presented with faulty evidence, and not sequestered. They were staying in the same hotel as a lot of the Crown witnesses, and drinking with them (and some of the local police) at night in the bar. They also had access to newspapers.

Given all this, Lindy says, it was ridiculous to expect impartiality. “Rumour fed rumour and speculation was rife,” The Weekly’s correspondent, Lenore Nicklin, wrote at the time. And the jury had access to all of it.

However, even without all that stacked against them, Lindy maintains, juries have an uphill battle. “Doctors, lawyers, sole business owners, teachers, government workers, police – basically anybody with a degree – is excluded or excused from jury duty,” she explains.

“And science is now leaps and bounds over the head of the average person.

“We’re giving juries very complex tertiary and even PhD-level forensics to try to decipher and decide whether a person is guilty or innocent … It’s not their fault if they get it wrong.”

It is a judge’s responsibility to ensure juries are not out of their depth, but Lindy believes that is no longer enough; that even judges struggle with some of the science.

“I think my case started highlighting this. Kathleen’s case has once again really slapped this in the public’s face. And people have gone, ‘Hang on, we were wrong about Lindy because we didn’t get all the information. Perhaps it’s time we did something about it.’”

Lindy proposes that, in cases where there is scientific or otherwise complex evidence, the jury be supported by a panel of experts who assess the evidence, and without bias or prejudice, decode it for them.

“These should be peers of the evidence,” says Lindy. “So, if it’s blood evidence, you have blood specialists looking at it. They look at it and say, ‘That’s inaccurate, that’s irrelevant, this is the only bit you can rely on.’ So that is the only piece of evidence sent to the jury.

“It needs to be a rolling panel of experts who are not always on duty. No one knows who is on which case, so they can’t be bribed. They can be both Australian and international.

“I think juries are good – I had actually sat on juries before all this happened.” But they need better advice.

“A lot of people think,” Lindy adds, “that if you go to court and tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth, you will be believed, justice will be served, but that is not the way it works. What I’m proposing won’t fix everything, but it will be a start.”

Lindy’s thoughts on this are beginning to gain more widespread traction. In the wake of Kathleen Folbigg’s pardon, Australian Academy of Science Chief Executive Anna-Maria Arabia said that the Academy hopes to work with the NSW Attorney General, Michael Daley, to develop a more science-sensitive legal system so that a miscarriage of justice of this magnitude is never repeated.

“This case has implications for the justice systems of every Australian state and territory,” she explained. “There is a critical role for independent scientific advice in the justice system, particularly where there is complex and emerging science.”

And Lindy believes there is a critical role for the public too, in advocating for this kind of reform. “In order to get something like this going,” she says, “the public needs to get behind a groundswell to give it momentum.

“People need to start these conversations with their friends and neighbours, and say, ‘It’s time we did something, this needs to change.’

“It was me way back then, but there have been many since. This can happen to anyone.”

All the public hysteria and legal bickering at the time distracted from the fact that, at the centre of the Chamberlains’ case, was a grieving mother who had lost her nine-week-old baby. And even now, as she pursues legal change, Lindy says, the loss of Azaria remains with her.

“For everybody, it’s different – how you get through grief,” she begins. “Your friends will often tell you that you’ll get through, you’ll forget. That’s rubbish.

“No one ever forgets. It’s a little bit like your school days. It’s part of you.”

“It doesn’t mean you’re still in your school days, it doesn’t mean you dwell on them every day, but they’re there, they’re part of you. You can never take that out. It’s taught you all sorts of things, it’s helped mould who you are. It’ll always be part of you. Grief is like that too.

“Some things become harder as the years go by that you would never have thought. Some things get easier. You can be going fine and see the movement of a head in a crowd, and it’ll hit you all again – you’ll never forget.

“Like a big operation – you don’t feel the pain anymore, but if you look down, there’s the scar. And every now and then you’ll feel that scar and it’ll give you a tweak, but it’s part of you now.”

Lindy still thinks of Azaria often.

“Of course I do,” she says. And when she first set eyes on her granddaughter, Amelia, it was as if Azaria had swum back into view. It was a shock, but then a delight.

“Seeing Milly as a baby was like being poleaxed,” she says. “I took one look at her face and she was so much like Azaria … She didn’t have violet eyes, I can tell you that. Azaria did, Milly didn’t. But everything else about her face was so like Azaria because she’s also so like her dad [Lindy’s son, Aidan] and me.”

What are Lindy’s children doing now?

Aidan, Lindy’s eldest, lives in Western Australia with his wife, Amber, and their three girls, Amelia (better known as Milly) who is 10, Alexa (Lexie), seven, and Alanie, five.

They call Lindy ‘Grammy’ and her husband Rick is ‘Cricket’ because “he’s chirpy and bright”.

“Aidan’s a sparky [electrician]. He and Amber run their own business,” Lindy says, and adds with a chuckle that “he’s had too many accidents recently to continue his favourite hobby, motorbike racing. He loves it though, and he’s doing his best to get his girls to ride.”

Their Aunty Kahlia, meanwhile, is encouraging their love of the water. Kahlia, who was born soon after her mother went to prison, and was fostered out for nearly three years, until Lindy came home, is a triage nurse with a post-grad specialisation in Acute Care and Emergency Nursing, presently living in the Virgin Islands.

Lindy’s second son, Reagan, is also a sparky. He lives not far from his brother in WA. Lindy believes he has PTSD. “He still has nightmares,” she explains, “though they’re getting further apart, of a dingo walking on him.”

Reagan was tucked up in his sleeping bag in the tent that night – he was just four years old – and the dingo did indeed walk over him, carrying his little sister.

Every one of Lindy’s kids has grown into a good, kind, smart human being in spite of the trauma they suffered when they were young.

Lindy still receives letters regularly from people who have been moved by her story. Many of the letters ask about forgiveness, a concept with which she’s had more experience than most.

“I’ve realised that forgiveness is not for the other person at all,” she explains. “We’re not God, we don’t have the power to forgive anybody. When I talk about forgiveness, I say, who’s the tenant in your head? Your mind is like real estate and if you’re dwelling on what someone else did, you’re giving them free tenancy.

“So forgiveness is for us, because if we don’t forgive and move on with our lives, everything we do from that moment will be poisoned and influenced by the person or thing that hurt us.”

It’s almost time for us to go, but before we do, Lindy opens one of the envelopes and reads a letter from a woman apologising for having not believed her at the time of her trial.

As Lindy reads, she sheds a tear, and we sit quietly for a moment.

“It takes a lot of guts to do that,” she says finally. “I think letters like this are absolutely beautiful.”

Read a longer version of this feature in the November 2023 issue.