Kerry Packer was not amused. He’d ordered a batch of pink-iced finger buns, his favourites, and eagerly awaited their delivery straight to his office. But when the treats with their soft white yeast dough, sultanas and shaved coconut arrived, they were missing a crucial ingredient – the large slathering of butter he craved.

“He was on a very strict diet due to his heart condition,” Pamela Clark, who joined The Australian Women’s Weekly’s Test Kitchen in 1969, recalls from her home in Fiji today. “I said to him, ‘We can make your finger buns, Mr P, but you can’t have butter’. He wasn’t interested after that.” It was testament to the might of The Weekly’s Test Kitchen that “Mr P” didn’t sack her on the spot. For the kitchen was perhaps the hardest worker on staff at his favourite magazine, and certainly the most valuable.

The Australian Women’s Weekly food history is undeniable. From beloved Women’s Weekly birthday cakes, to meals based on wartime rations, the Women’s Weekly Test Kitchen and its recipes have been part of Australian history and the nation’s families for generations, with cookbooks collected and passed down from parent to child.

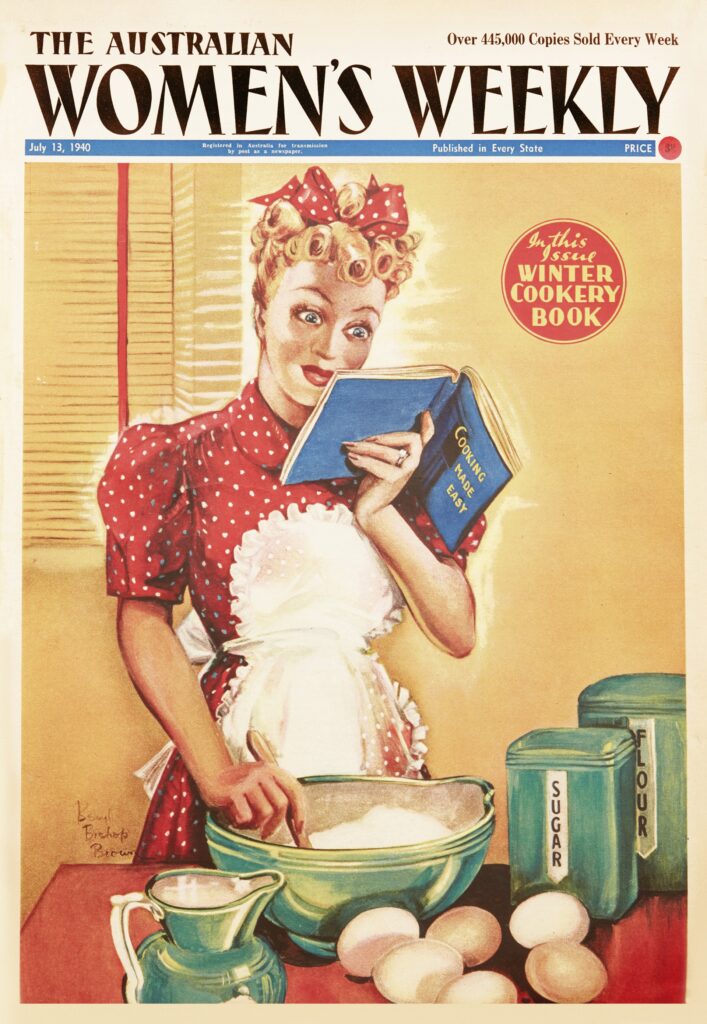

Since its inception in 1933, tried and tested recipes had not only been a staple of The Weekly but shaped the way readers at home – and abroad – looked at food, how they ate, and the way they prepared their favourite recipes.

The Women’s Weekly food history is evident in how readers have always turned to The Weekly’s food pages for inspiration, from mock meats invented during the austere times of WWII, to the arrival of the classic Children’s Birthday Cake Book in 1980. In recent years, we’ve embraced cultural diversity, while fail-safe cookery methods help home cooks nourish family and friends and forge new connections through the love of a shared meal.

“Since the beginning, The Weekly has always answered the question of ‘What am I cooking for dinner tonight?’” says Lyndey Milan, the Food Director from 2000 to 2008. “We were at the forefront, bringing new approaches and flavours to our readers while keeping the loyal longtime readers feeling loved. It remains a staple through trust. Trust that the recipes will work, that it is not fad or fashion, but authentic and influencer-free.”

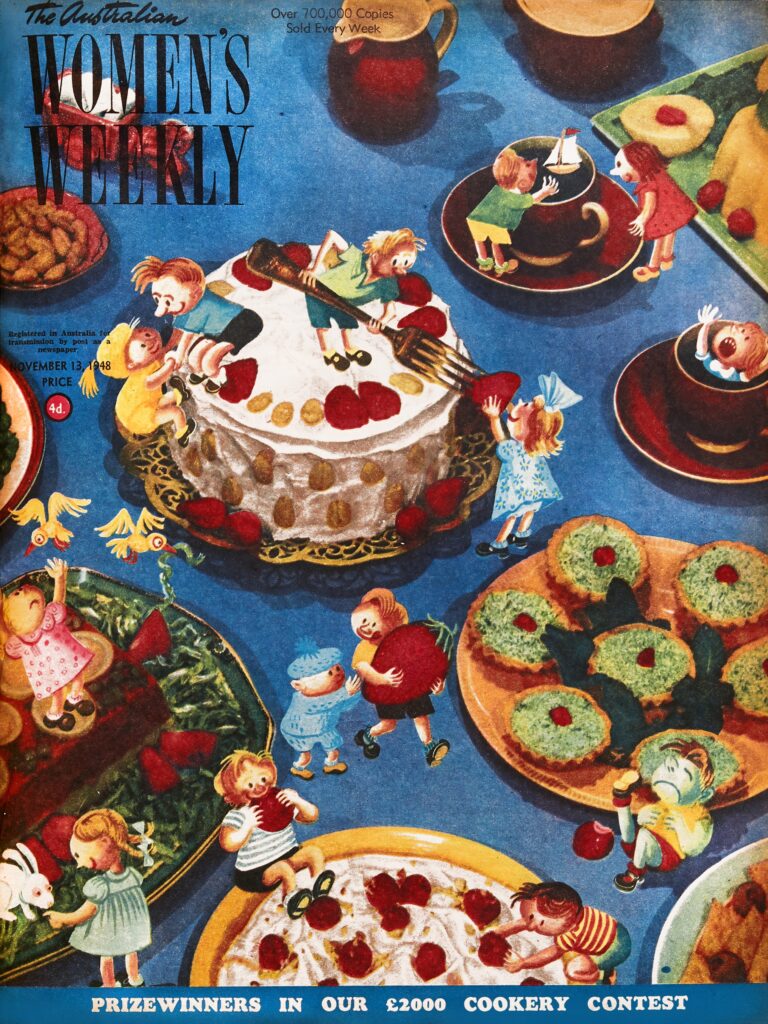

That’s because the magazine itself, according to food historian Lauren Samuelsson, was the original food influencer – the pages playing the role that Facebook and Instagram would take decades to follow. “The first cooking competition came in the second issue and had people winning five pounds, which in 1933 was a ton of money,” says Lauren, who spent five years studying The Weekly’s influence on Australian food for her PhD. “They ended up scaling it back to one pound. I don’t think they’d realised how many people would enter! It really showed that women were keen to share their knowledge and show off.

“The pages of The Weekly made it easy for them to do that. They started a community, talking to each other through food, sharing recipes they were proud of. It was like the 1930s version of social media, as it was a chance to show how much you knew about food.”

While meals in the ’30s were very “British”, leaning into the “meat and two veg” cliché, a delve into the archives shows adventurous flavours starting to rear their heads too with the publication of a smattering of surprisingly authentic Cantonese recipes. However, not long after surviving the lean Depression years, World War II would change everything in Australian households once more.

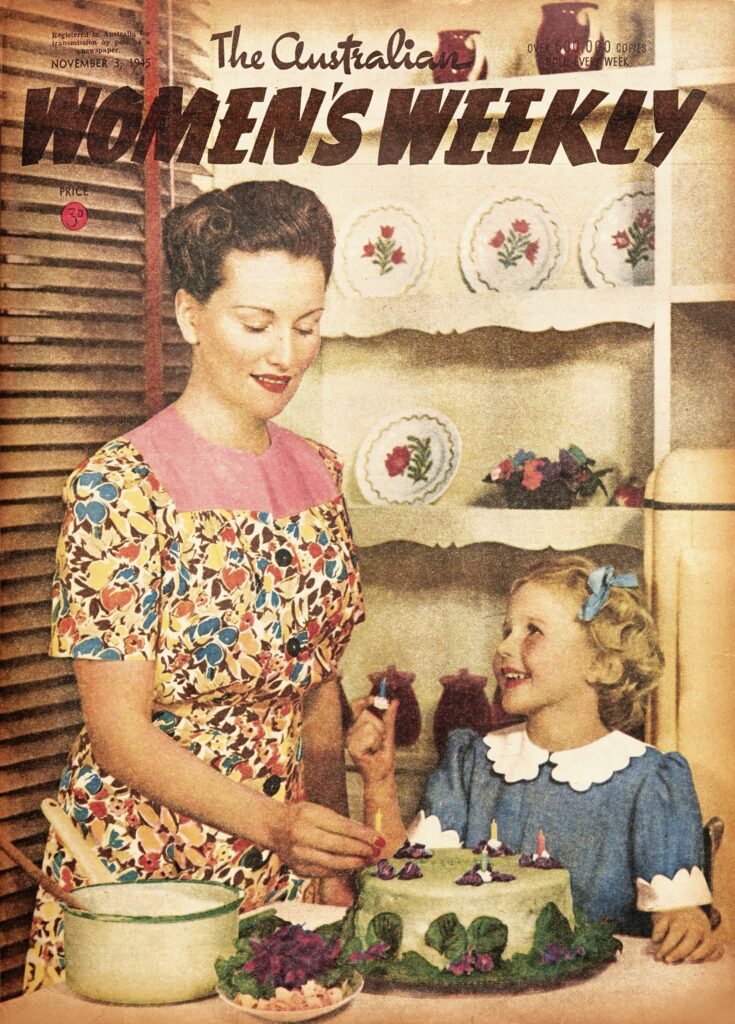

First, rationing meant that supplies – especially when it came to meat – were short on the ground. Secondly, a wave of women entered the workforce, meaning time to spend in the kitchen was limited for the first time in history.

Luckily, The Weekly was there to help readers in these new, uncertain times. Recipes for “mock meat” were devised to replace a dinnertime staple. And cuts from animals that would have formerly seen Aussies turn up their noses were introduced.

“People were trying to hold onto the foods important to them, even though they couldn’t get those things,” explains Lauren. “Chicken was really expensive so transforming rabbit, considered quite low on the scale of meat, or offal or tripe, which were often dressed up as chicken, turned into a status symbol. During the war years, it was about keeping morale high. ‘We don’t have these things anymore, but we can create them, it’s fine!’

“In the 1930s, there’d be a menu for dinner which was four courses. Then, suddenly it changed to meals that were easy and would last a few nights. There was also a change in the methodology of cooking itself. There were a lot more casseroles and ‘set-and-forget’ meals, which helped stretch ingredients.

“Also, there was real focus on nutrition during the war because the government was trying to make sure the population remained healthy despite shortages. So now, not only were women responsible for feeding their family, they were responsible for the health of their family and had to know all about nutrients, calories and more. It wasn’t about being full, it was about, ‘Am I getting the right amount of vitamin B?’” Once more, The Weekly stepped in to help – with pages devoted to time-saving recipes and the foods that would nourish and sustain.

As a new decade dawned after the war, The Weekly and its influence on the world of food pivoted again. Pamela recalls her mother buying the magazine during the 1940s and ’50s to experiment with new flavours.

“I remember when she made coleslaw for the first time, it was a big deal in the family,” she says. “She had to have a wooden bowl and had to rub the bowl with garlic and so on. Spaghetti bolognese came into our household when I was about 10. We had curries with apples and sultanas in them, sweet curries, but they were pretty adventurous.”

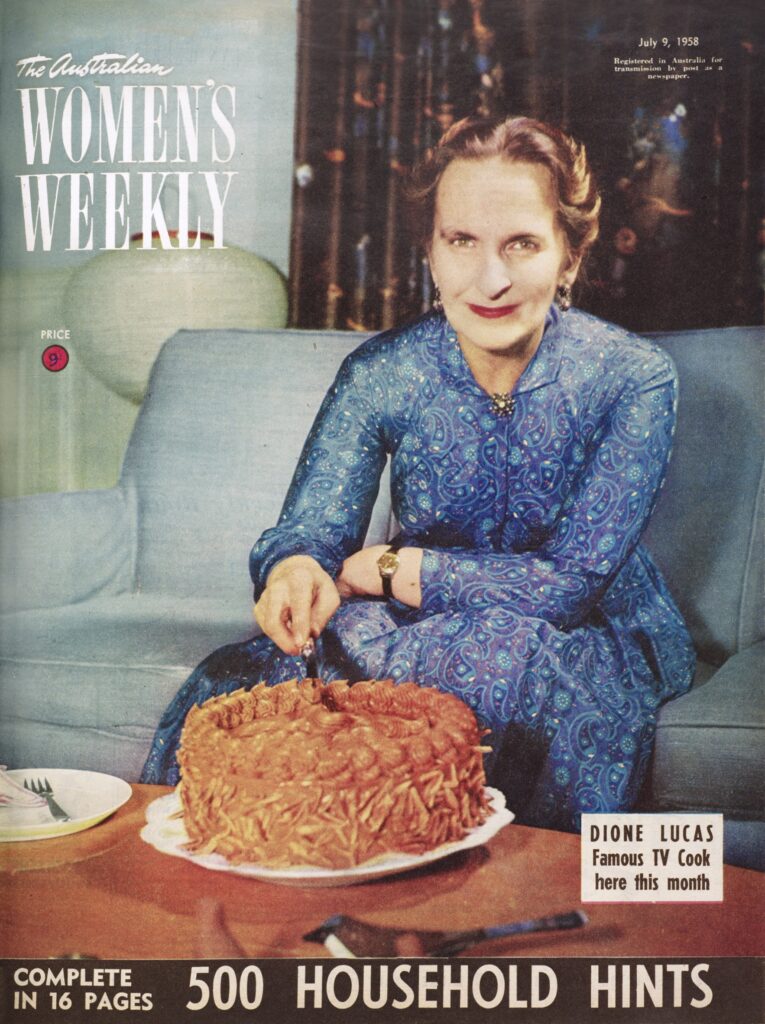

The wave of European migration post-war was also having an effect. Traditional French, Italian and Greek recipes were given an Aussie twist in The Weekly. There was an emphasis on glamour and dressing foods up to make them look “fancy”. Meanwhile, an obsession with all things American led to convenience foods becoming staples for the first time, with boxed cake mixes making their way to store shelves.

And soon another American cultural phenomenon hit our shores: the rise of the teenager. By the early 1950s compulsory education, a post-war economic boom and a wave of Hollywood films saw teenagers become a powerful force in both the media and society.

Certainly, The Weekly was abreast of this, and in July 1954, Debbie the teenage chef made her first appearance in the magazine’s pages, showing girls how to make a sponge along with a variety of fillings. While she never showed her face (we never learned who “Debbie” truly was), this teenager would prove her worth as a social influencer in her own right. As her tenure continued well into the 1960s, she’d teach basics such as “how to boil an egg”, while also giving fun ideas for Hawaiian luaus and other parties that “boys” might also attend, with photographic examples.

Food photography at the time was expensive – particularly in colour, as Debbie’s recipes were. In 1962, Sir Frank Packer had spent a small fortune creating a custom-made kitchen in the centre of Sydney which was decked out in pinks and blues and housed then-cutting-edge technology. It was here that Pamela joined The Weekly as Chief Home Economist, under the tutelage of esteemed cookbook author and Weekly Food Director Ellen Sinclair, who served in that role for more than 20 years. And every time they included photographs of a recipe, she recalls, “the phones never stopped ringing … the recipes that weren’t photographed were hardly ever cooked.”

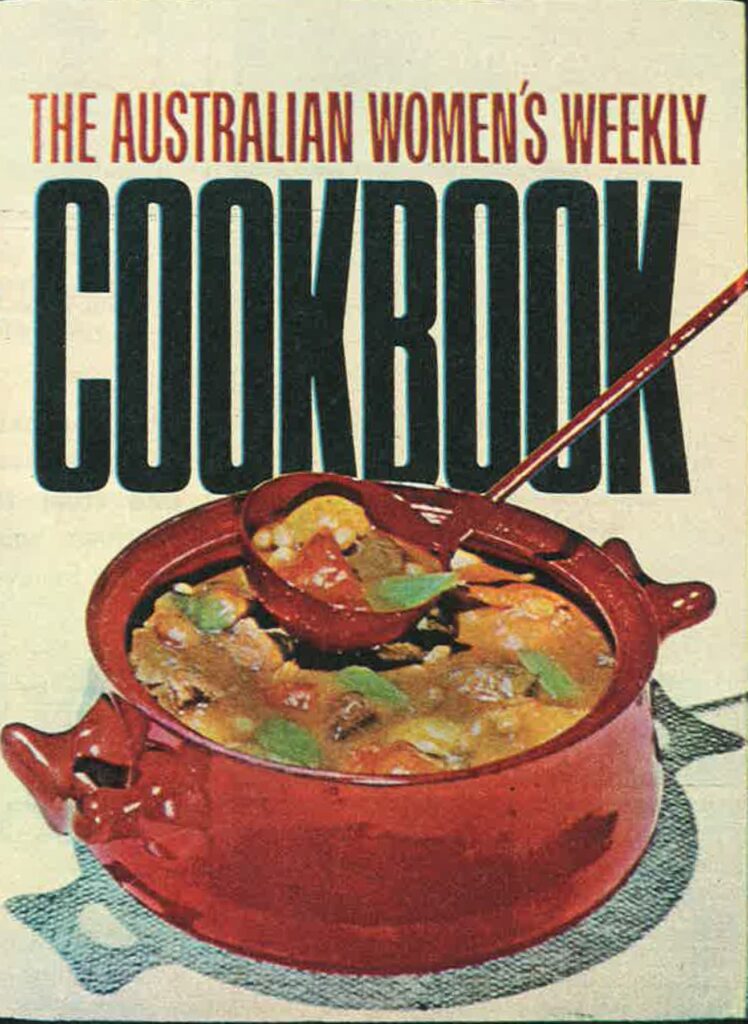

This accounted for the runaway success when The Weekly began publishing cookbooks from 1955, adds Lauren. Every recipe was photographed.

“They were really beautiful to look at and people hadn’t had that in food before,” she explains. “If you looked at cookbooks, there were just a list of ingredients and instructions. There might have been a little drawing, but no photographs. The Weekly put the magazine into the cookbooks – it had these lovely pictures, the paper was glossy – aesthetics matter. Also, the recipes worked, and that’s what made them so successful to begin with.”

“I used my pocket money in 1968 to buy first the original Margaret Fulton Cookbook and then the big Australian Women’s Weekly Cookbook,” recalls Lyndey. That sparked her passion – and later her career – in food. She would also pull out the recipe inserts that appeared in the magazine to cook for family and later for friends.

Certainly, the late 1960s saw a shift towards home entertaining, and the types of recipes – and accompanying cookbooks – became more experimental. Any time a restaurant with a “new” type of cuisine opened, “Mrs S”, as Pamela and others at the Test Kitchen called their leader, would invite the head chef in to show the team how they prepared these dishes.

“We never tried to be ahead of the game, we tended to follow a trend,” says Pamela of what would prove a winning approach for decades to come, including when she took over from “Mrs S” in 1983. “We’d wait until there were restaurants established in suburbs. We’d do the book when people were used to the tastes. Thai is a good example.” And so Women’s Weekly food history also became a mirror of changes in taste, as well as an influencer.

Similarly, adds current Food Director Fran Abdallaoui, a slew of well-known Aussie chefs have stated that their love of cooking started thanks to The Weekly. For Curtis Stone, it was due to a “beautiful chocolate caramel bar”.

“I got it from The Women’s Weekly Cookbook my mum kept,” he recalled recently. “I remember flipping through it thinking, ‘Oh, that looks good.’ Then I got a recipe out of one issue and then I got another recipe for the same sort of thing. I combined the two recipes somehow and I was like, ‘I developed my own recipe!’ I cooked it all the time, it was delicious!”

From the mid-1930s, the entire senior staff of The Weekly was female, a feat far ahead of the curve. Fast forward a few decades, and a growing number of women were routinely juggling work both inside and outside the home. When Crockpot – the original slow cooker – was released in America in 1971, it almost instantly sold out. Like other US exports, it wasn’t long before Australian women were clamouring for the labour-saving invention. As a result, The Weekly not only populated the pages with slow-cooker recipes, but in 1972 released The Busy Woman’s Cookbook, designed to cater to those looking for quick and easy meals to cook at the end of a long workday. While Lauren jokes that the original version wasn’t that much less complicated than traditional recipes found in The Weekly, this quickly changed with a series of cookbooks aimed at working women, which were eagerly snatched off the shelves.

Another Test Kitchen innovation around this time was a recipe card collection, housed in a branded plastic box, with a photo on one side and the recipe on the other. Again, the phone rang hot with readers keen to know where to buy the cards – at that time only available via mail order.

This wasn’t the only shift. Diet culture had been simmering since the late 1950s, but by the ’70s had gripped women around the nation. Where the war years had seen an approach to nutrition aimed at helping readers keep their families healthy, these later years were all about low-fat, low-sugar, low-carb, low-calorie diets in a race to be slim.

Lauren recalls a dieting competition The Weekly ran in the 1960s where readers sent in their meal plans along with accompanying before and after pictures. “There were wild diets,” she says. “And some that were just unhinged. One was the spaghetti diet, where you can eat spaghetti and still lose weight.” Women’s Weekly food history certainly has some odd moments.

“We definitely tried to devise diets and followed health trends but if it was really extreme, we didn’t do it,” says Pamela of how the magazine responded to the demand for weight-loss recipes. In the ’90s, the magazine ceded to popular demand to include calorie counts. “I hated it,” she grimaces now. “I just thought to myself, people should be able to make their own decisions about what they eat but I was beaten down.”

“We’ve taken a very considered approach to health – both in the magazine and our cookbooks,” adds Fran, a part of the Test Kitchen since 1999. “We’ve always consulted experts to vet our nutrition advice and make sure what we’re offering readers is as trusted as our delicious scone recipes.”

Speaking of scones, while diet-friendly recipes may have been in demand, so too were the baked goods the Test Kitchen was – and remains – renowned for. By 1980 Pamela had a little boy and was making the rounds of kids’ parties. “I’d see the attempts the mothers – and sometimes fathers – had made at cakes and some were atrocious. But nobody cared – the kids loved them!”

It sparked an idea. What if they had a range of tried and tested (by the 1970s The Weekly’s famous triple-testing standard had been introduced) cakes that would reflect the hobbies, interests and popular characters that kids adored?

And so The Australian Women’s Weekly Children’s Birthday Cake Book was born. It was released in 1980, and Pamela was sure it would be an instant hit. She was wrong. “As opposed to previous Weekly cookbooks, which had sold their socks off, it didn’t sell well in Australia at all,” she laughs of what initially seemed like an expensive misfire. “But it sold incredibly well in the UK, South Africa, New Zealand, Canada, and then finally Australia caught up. I guess the rest is history.”

To date, over 80 million copies of the book have sold worldwide. The cakes themselves have starred on TV screens (including an appearance of the Rubber Ducky cake in hit cartoon Bluey). Personalities from former NZ Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern to comic Hamish Blake have taken to social media to post their own attempts to recreate the cakes for their kids.

When the Bendigo Art Gallery held an exhibition celebrating The Weekly’s 90th birthday earlier this year, over 3000 locals sent in pictures of themselves with their own cakes from their childhood: An entire wall of the gallery was taken over by these snaps, a highlight for the thousands who visited the exhibition.

Lauren believes that the reasons behind the recipes’ lasting success are as relevant now as they were in 1980. “The cake book was an opportunity for food to be representative of a child’s identity,” she explains, “but it was also an opportunity for parents to show how much they loved their kid. In the early 1980s, lots of women had moved into the workforce and there was maybe a bit of mother guilt there. ‘Well, I’m not there for my kids. How can I show them I am still a good parent?’ There was anxiety that probably still is there.”

One person who has a visceral recollection of having a few of these iconic cakes is Julie Goodwin, who served as a columnist for The Weekly after her historic 2009 MasterChef Australia win. “Mum always had The Weekly in the house and certainly the birthday cake book. We had a few of those made,” she says with a smile. “Mum used to not only cook the recipes, but she’d also use the lunchbox ideas – we had some pretty interesting lunchbox fare!”

When Julie received the call to join The Weekly team, “I cried,” she says. “It was the go-to magazine for food. It was the food title of choice for me. I was so overwhelmed to even be on the radar of this publication that had been part of my life for so long.” MasterChef had given her a public platform, says Julie, but it was The Weekly that would give her the building blocks to have a career in the industry, which included writing the first of many cookbooks.

“I learnt at the feet of giants. The Weekly is, quite simply, the gold standard of recipe writing.”

Julie Goodwin

Julie says of the hands-on training she received from Fran. “The Weekly is, quite simply, the gold standard of recipe writing. One of my driving principles is that my recipes must work, they must be achievable. And that’s very much a Women’s Weekly priority. In my 10 years as a columnist, I never saw photographic trickery. Everything was genuinely cooked to the recipe and photographed in real time. I loved the authenticity.”

This is something all who have spent time in the Test Kitchen proudly attest to. And it’s why The Weekly continues to answer the question, for thousands around the country, of “what’s for dinner, for lunch, for snacks, for parties, for picnics and more?”

“The Weekly is a friend in the kitchen,” says Fran of the lasting success. “Food unites us all, no matter where we come from. Food is our love language, and there is nothing more joyful than cooking for someone you love.”