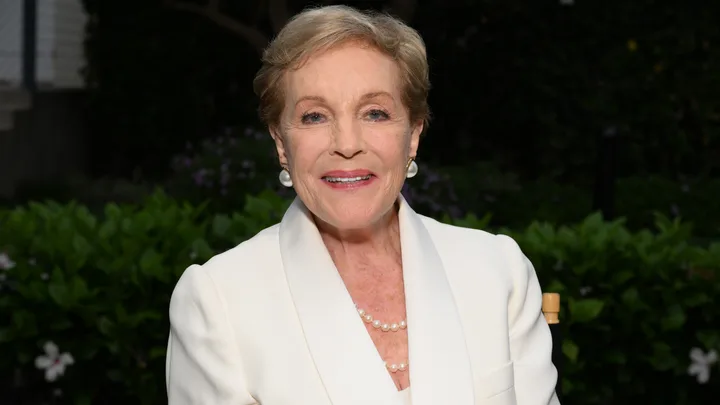

In March 2025, The Sound of Music turned 60. In October its star, Julie Andrews, will be 90 years old. The Weekly honours two icons of the cinema as they continue to bring joy to new generations.

Walking onto the 20th Century Fox lot in Hollywood on a sunny March morning in 1964, Julie Andrews was as excited and anxious as the seven children awaiting her. Just 28 years old, she was a rising star in musical theatre. However, she had only made two films (1964’s The Americanization of Emily and Mary Poppins) and neither had yet been released. To many people on the lot that day, she was a complete unknown. It was with some trepidation that she approached the vast studio where the soundtrack to Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The Sound of Music was about to be recorded.

“To walk in through the heavy door and see and hear 70 musicians tuning their instruments, practising a phrase, leafing through a score, is enough to make your stomach somersault with nerves – but it’s also a thrill,” she wrote in her autobiography, Home Work.

The seven ‘children’ (the eldest, Charmian Carr, who played Liesl, was actually 21) had been rehearsing for a week. They were all eager to meet the woman who would play their much-loved governess, co-conspirator and finally ‘mother’ in the film version of this already popular musical.

“I hoped that I could live up to their expectations,” Julie added. She needn’t have worried. She already had one young afficionado among the group.

Julie Andrew’s Australian co-star

Nicholas Hammond, who played Friedrich, was 13 years old and a somewhat seasoned child actor. He had played roles on Broadway, on television and in the film of William Golding’s novel, Lord of the Flies. He knew exactly who Julie Andrews was and for four years, he had longed to meet her.

Nicholas had been nine years old and walking with his family through the West End in London when they’d spied a queue for tickets at the Theatre Royal. That night, they were told, would be Julie Andrews’ final performance as Eliza Doolittle in My Fair Lady. Nicholas’ mother procured the last two tickets.

He remembers the lights, the music, Julie’s clear, strong voice. “And I thought,” he tells The Weekly, “that just looks like the most wonderful thing anybody could do with their life. She was in this brilliant play, wonderful music, audience adoring it and cheering and applauding. The excitement in the theatre was huge. I picked up on that and I thought, this is what I want to do … So Julie Andrews was the embodiment, to me as a child, of the ultimate. Of if you’re really good at what you do and if you’re in the right show, that’s what it can be … I felt in my gut, this could be a wonderful, wonderful life. And I was right.”

The “extraordinary” voice of Julie Andrews

Nicholas remembers the seven young cast members standing in the studio, four years later, waiting to hear Julie sing.

“There were seven microphones lined up in front of this immense orchestra with a conductor. It was pretty terrifying to a boy who had never sung in his life. And Julie was standing in a little booth that looked like an old-fashioned phone booth with glass walls.

“She was in there with her microphone, but we could hear her. Her mouth would open and this extraordinary sound would come out that just seemed otherworldly. I thought, how does a human being create that sound? I was transfixed. It was an extraordinary gift – watching her sing and later act. I listened to her, and I watched her facial expressions and her gestures. I just hung on her every word.”

It wasn’t long, though, before Julie broke through that sense of awe. She and the young cast became fast friends. Julie had always enjoyed the company of children and by then, she and her stage designer husband, Tony Walton, had a 14-month-old daughter, Emma, who came with her on the road.

“I had never worked with seven children before,” she explained in Home Work. “I imagined they might be even more nervous than I was. So I spent as much time as I could telling them stories, making faces at them behind the camera when Bob [director Robert Wise] needed a good close-up, and generally trying to put them at ease. The adorable grin I elicited from Duane Chase [Kurt] in Favourite Things was reward enough.”

A mentor to the younger cast members

Nicholas believes the attention she paid to each of them, on and off the set, was an indispensable ingredient (like Mary Poppins’ spoonful of sugar) in the film’s magic.

“She was really giving of herself with the children – far more than most people would be in that situation,” he explains. “She went out of her way to spend as much time as she could talking to us, playing with us. Teaching us songs, teaching us riddles and jokes.

“Now that I know what the responsibility is like when you’re the lead in a movie [Nicholas went on to play the original Spider-Man, among other roles], I admire even more that she had the grace and generosity to give us that much attention. She could easily have done the scene and walked straight off to her dressing room. But there was method in her madness. In the movie, we were all supposed to adore her, and we did adore her. Julie was determined that we were all going to be a happy family together on the film, and she made it that way.”

The true story behind The Sound of Music

T he cinematic adventure on which cast and crew embarked that day had its roots in Austria 25 years earlier. There was a real Captain Georg von Trapp, who lost both his navy (after World War I) and his wife (Agathe, to scarlet fever). He had seven children and limited resources with which to care for them.

The family moved to a villa in Aigen, outside Salzburg. It was while they were there that a novice from the Nonnberg Abbey arrived to work as the children’s governess. Her name was Maria Kutschera, and as the Baroness (played by Eleanor Parker) notes poignantly in the film, she was “a young lady who [would] never be a nun”. At the risk of spoiling this for newcomers to the story, Maria and Georg did fall in love.

Agathe and the children had always played and sung music. Maria expanded their repertoire and took the family choir on the road. They found a following both for their classical and Austrian folk repertoire, but their popularity sealed their fate.

“They started with absolutely nothing”

Adolf Hitler had long dreamed of reuniting Germany and Austria, and Georg von Trapp was part of a pro-Austria, anti-Nazi movement. As the Anschluss (or annexation) proceeded and Hitler’s troops marched across the border, Georg refused an official appointment to the German navy. Then his eldest son, Rupert, refused a position in a hospital in Vienna, realising it was only available because so many Jewish doctors had been deported and arrested (approximately 65,000 Austrian Jews would be murdered in the Holocaust). Finally, the von Trapp choir turned down a number of official invitations to sing for the German Reich – the last was at Hitler’s birthday party – and realised that they had to leave the land they loved.

In August 1938, the von Trapp family packed rucksacks, left home before dawn and caught a train to Italy. It was just 24 hours before the border was closed. From there, they caught a steamer to London and on to New York. They arrived (almost 12 of them then, as Maria was expecting her third child) with just $4 and barely a word of English between them.

“The stakes were incredibly high,” says Nicholas, who made a documentary about the family. “They’d have been killed as traitors if they’d been sent back. And they started with absolutely nothing. They busked on street corners, then they bought an old school bus and went from town to town.”

Hammerstein finds his inspiration for The Sound of Music

Luckily the von Trapps’ arrival coincided with an American folk music renaissance, and they found an audience. They saved what they could and bought a dairy farm in Vermont. Once settled, Maria wrote a memoir which came to the attention of Oscar Hammerstein II. With an enterprising mix of imagination and history, he and fellow composer Richard Rodgers created a musical. Later, Robert Wise would make into the most successful musical film of all time.

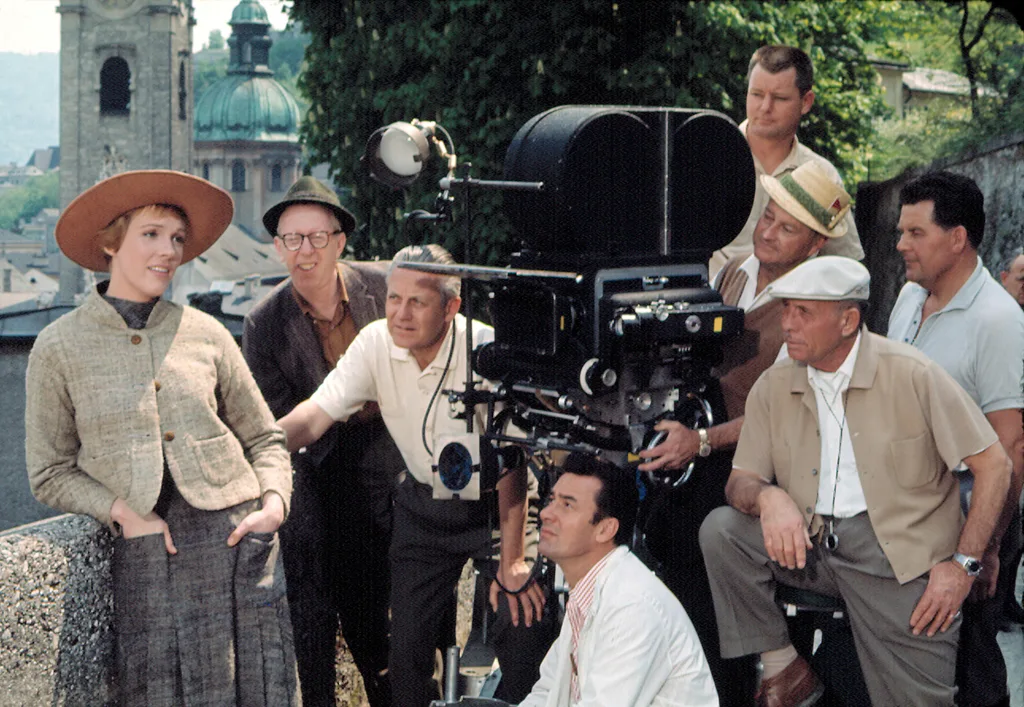

Principal photography for The Sound of Music began in Hollywood at the end of March ’64. In April, the cast decamped to Salzburg. There, the children and their mothers moved into the Hotel am Mirabellplatz. Julie, Emma and Emma’s nanny, Kay, had some privacy at the Hotel Österreichischer Hof (now the Sacher). The other principal cast lived it up at the ritzy Hotel Bristol.

It wasn’t long, Julie recalled in her memoir, before Christopher Plummer became “renowned for his late-night performances at the piano in the hotel bar. In his youth, he had trained to be a concert pianist, and he was very good indeed. He apparently spent his evenings at the bar, getting smashed and playing Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky until the wee hours.”

Troubles on The Sound of Music set

Cast and crew learnt fairly swiftly that the town that had been home to Mozart and the real-life von Trapp family also had the seventh highest rainfall in Europe. It rained, and then it rained – on roses and cameras and often on the sodden cast.

“For the Alpine scenes,” Julie recalled, “our equipment trucks were parked at the foot of whatever mountain we were filming on. There were no roads. Just fields and rutted tracks. The camera equipment had to be carried up on an ox-drawn cart and the rest of us had to walk … Once we reached the designated location, tracks were laid and cameras were set up, then temporarily covered with tarps. We actors would settle somewhere, under a tent or in a barn if there was one, to wait out the weather … Many days went by when we only got a single shot.”

When the clouds did part for a moment or two, the cast would “throw off our blankets and dash out, only to do about two seconds’ worth of filming, if we were lucky, before the weather closed in again”.

During breaks, Julie ran lines with the children, practised the guitar (which she was learning) and joined in singalongs with producer Saul Chaplin and choreographers Marc Breaux and Dee Dee Wood. They called themselves the Vocalzones after Julie’s favourite throat pastilles.

Shooting the memorable opening sequence

It was, however, a relatively sunny day when Julie and the crew gathered in an Alpine field to shoot the iconic, long-pan opening scene. The crew hid behind trees and Julie waited in the field until Bob shouted ‘Go’ through a bullhorn. Then Julie would begin to twirl and a helicopter carrying a camera operator would swoop towards her.

“It would circle me,” she later told Vanity Fair, but as it rose to leave, “the downdraft would knock me flat in the grass.” There were several takes and each time she’d pick herself up “spitting hay and mud and straw and God knows what. But it was an amazing shot – it looks so seamless”.

Falls and falling behind

By this time, largely as a result of the weather, the production was three weeks behind schedule and substantially over budget. And there was still more to shoot. The studio was losing patience, as was their host farmer, who claimed that filming was disrupting his cows’ milk production.

Yet they persevered. In another memorable scene, the seven little von Trapps and governess Maria were tipped from a boat into the river. They very nearly lost the youngest member of the cast.

Minutes before the cameras rolled, the assistant director whispered to Julie, somewhat urgently, that Kym Karath, who was just seven years old and played Gretl, couldn’t swim. Julie was tasked with “getting to her as quickly as possible”.

On the second take, the boat rocked particularly roughly, tipping Julie and Kym in opposite directions. “I have never swum so fast in my life,” Julie confessed, and added that “Little Kym threw up all the water she had swallowed, and we bundled her in blankets and made a big fuss over her … She was being very brave.”

Christopher Plummer’s emotion number

Back in Hollywood, one of the final scenes to be shot involved the Captain (following that rather emotional interaction at the river) joining his children to sing the film’s title track. Unlike Julie, Christopher Plummer had kept his distance from the young cast throughout the production, and Nicholas suspects this was a clever ploy. He recalls that, when the Captain’s voice haltingly joined them, some of the children had genuine tears in their eyes.

“Oh gosh, that was a hugely impactful scene,” Nicholas says, “particularly for the older ones of us. It was also fairly late in the shoot, and I remember thinking, this is all about to end and I might never be in the same room with these people again. I mean, little did I know that 60 years later I’d still be going to reunions. But I wouldn’t be there with the director and the crew. I was old enough to think, we finish in a couple of weeks and this absolute dream that I’ve been in the middle of for eight months will be over. And that was enormously sad as well.”

The Sound of Music makes its mark

The Sound of Music premiered in March 1965 to mixed reviews but became one of the most successful cinema musicals of all time. The young cast members remain in touch. They’ll come together this year to celebrate Charmian’s birthday (she died in 2016), and Nicholas will be in Salzburg in October (with at least one of the real von Trapp family) to help the town celebrate the 60th anniversary of the film, which still draws thousands to climb its mountains and ford its streams.

Nicholas Hammond has never stopped acting and writing. He lives in Australia and recently toured with partner Robyn Nevin’s production of the Agatha Christie mystery And Then There Were None. Julie Andrews won an Oscar for Mary Poppins and was nominated for another for The Sound of Music. Since then, she’s had the freedom to choose roles as diverse as Sarah Louise Sherman in Alfred Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain, Queen Clarisse Renaldi in The Princess Diaries, the dishevelled and desperate Nanny in Eloise, the gender-bending titular character of Victor/Victoria and the mysterious Lady Whistledown, narrator of Bridgerton.

The magic touch of Julie Andrews

Julie’s “huge blended family” includes her eldest, Emma, two adopted daughters, Amy and Joanna, who were born in Vietnam, and a tribe of stepchildren and grandchildren.

In 1997, following a botched operation, Julie lost her perfect four-octave singing voice. At the time, it plunged her into depression, but she emerged to explore new creative ventures, writing books for adults and children, and creating a podcast with Emma.

“My God, I’m one of the luckiest ladies alive,” she told Vanity Fair in 2022. “I recognise how very, very lucky I’ve been.”

Sixty years later, The Sound of Music also finds ever new audiences. Its secret, like Julie’s perhaps, involves a little luck but a great deal of talent.

“It’s easy to say it’s got great music and good actors, but lots of films have that,” Nicholas ponders. “I think there’s something about the alchemy – the mix of ingredients and themes: Love of country, love of family, love of a woman for a man and children for their parents; a sense of duty and honour, doing the right thing and being courageous when you’re put to the test. No matter who you are, you would like to think that, if you were put into that situation, you would behave the way they behaved. I think that touches a nerve with people.

“Then,” he adds, “there’s Julie Andrews. I think that, along with beautiful execution and universal themes, the film has Julie. She has a great deal to do with The Sound of Music’s success.”

This article was originally published in the April 2025 issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly. Subscribe so you never miss an issue.