The Larrimah Hotel, located in the Northern Territory, is officially on the market.

The notorious pub is tied to an unsolved murder that occured in the tiny town of Larrimah in 2017.

In the eight years since then, the case has become a worldwide phenomenon.

It’s partly thanks to the 2023 documentary series, Last Stop Larrimah.

But it’s also because of journalists Caroline Graham and Kylie Stevenson. The two created a hit, Walkley Award-winning podcast in 2018 and released a best selling book in 2021 – respectively titled Lost in Larrimah and Larrimah.

In October 2021, they wrote exclusively for The Weekly about their work. Read their article in full below.

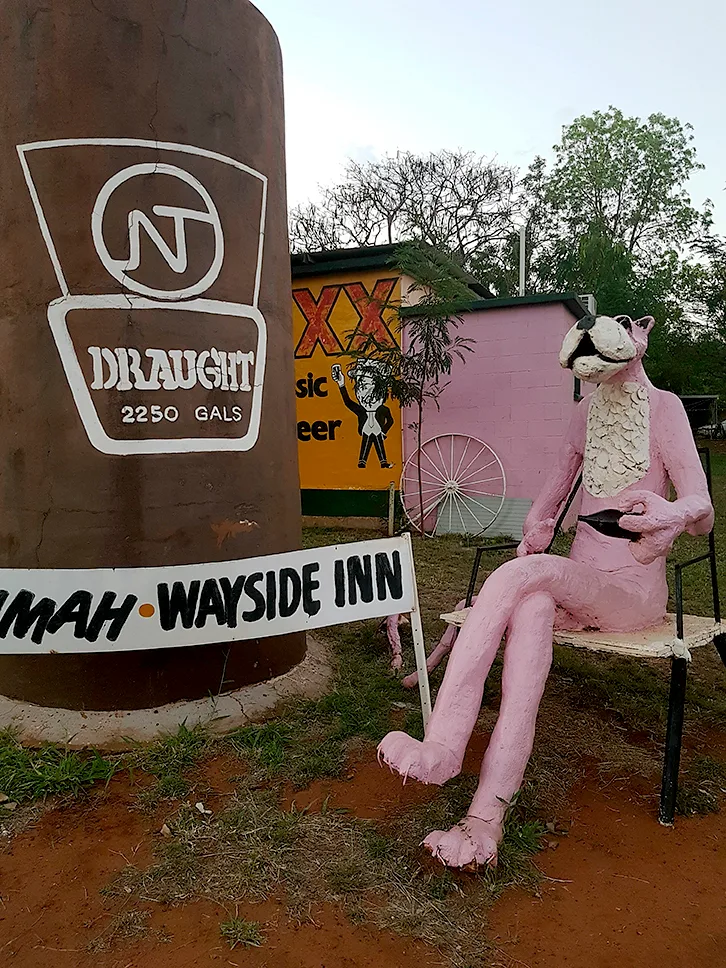

It was late on Sunday afternoon in 2018 when we first rolled into the dying town in the middle of the Northern Territory. The sun’s arc had settled into a spectacular orange over the bush but the temperature still hovered around 35 degrees. There was no one around as we pulled up next to a giant Pink Panther lazing in a deckchair beside a five-metre tall concrete statue of a beer bottle.

Where is Larrimah?

This is Larrimah: a tiny town perched on the edge of the Stuart Highway, about 500km south of Darwin. It’s what they call Never Never country, a harsh, scrubby landscape full of wild donkeys, death adders and the occasional sinkhole.

Our accommodation, the Larrimah Hotel, also known as The Pink Panther, looked like it had been plucked from the collective Australian imagination: a rusting tin roof topped a wide verandah and the building was painted bright pink. Inside, every wall was covered with quirky signs. War relics and more Pink Panthers battled for shelf space around the main bar, which claimed to be the highest in the Northern Territory. Out the back was a maze of aviaries and enclosures filled with emus, crocodiles, wallabies, snakes, squirrel gliders and hundreds of birds.

When the bartender, Richard Simpson, showed us to our room, he stopped by a small pond to introduce us to a croc with no eyes called Ray Ray. His enclosure was about five steps from our pink room.

We were there because one of the town’s 12 residents, 70-year-old Paddy Moriarty, had gone missing three months earlier. The circumstances were bizarre, even for Larrimah – a place that is steeped in strangeness – and we were hoping to get to the bottom of what happened, and how it might affect this hamlet hovering on the precipice of extinction.

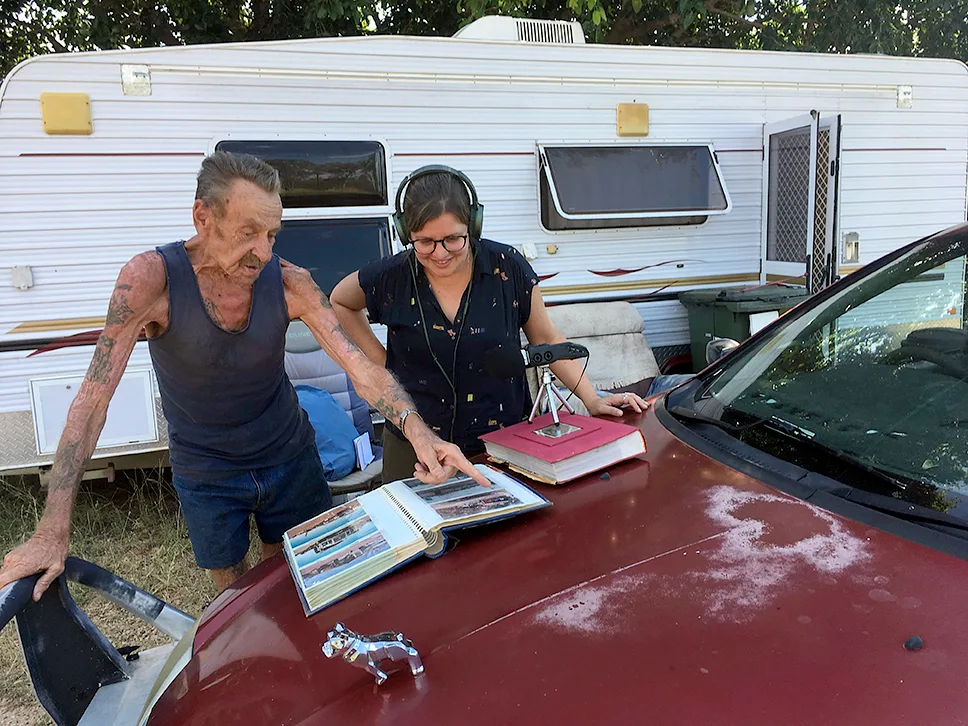

Barry Sharpe (now deceased), the publican, was expecting us. He’d lived in Larrimah for 28 years at that point, and had been running the pub for the last 14. The zoo was the result of Barry’s lifelong animal obsession. We tracked him down sitting at a bar table nursing a cup of tea.

“We’re making a podcast about Paddy,” we told him. “Maybe we’ll write a book, too.”

“What’s a podcast?” he asked. We explained it and Barry shrugged. We weren’t the first reporters to turn up, and we wouldn’t be the last. But perhaps we were more acutely aware of the town’s loss than most journalists, because it cut a little closer to home. Kylie had spent a few weeks in Larrimah the year before Paddy went missing. She’d sat with him and Barry on the verandah of the pub, drinking beer and exchanging stories.

“It’s not the same here without him,” Barry said, nodding at a bar stool in the corner. In thick texta someone had written on the sign above it: Paddy’s Corner.

Is Larrimah a true story?

Any missing person leaves a terrible absence. In a town of 12 people, the absence was more obvious than most.

It was a story that gripped Australia – equal parts tragedy and incongruity. On December 16, 2017, 70-year-old Paddy Moriarty and his dog, Kellie, vanished. Paddy had been drinking at the Larrimah Hotel, and around 6pm he jumped on his quad bike, Kellie on the back, and drove the 400 metres home. When he didn’t show up at the pub for a few days, locals alerted police. And when officers searched his house, days later, they discovered everything was as it should be. Paddy’s hat, wallet and keys were all on the table. There was dinner waiting, as if ready to be heated up. There were no signs of a struggle. But there was also no sign of Paddy or his red Kelpie, and nobody has seen them since.

There are a lot of ways to die in the bush – snakes, spiders, the occasional crocodile. The landscape around Larrimah is pockmarked with sinkholes and old war bunkers. The police spent days scouring the area for anything that might tell them what happened to the Irish-born man who’d moved to Australia in the 1960s. Helicopters whirred overhead, volunteers walked shoulder to shoulder, and police zoomed along every dirt track on motorbikes.

Police entertained all the possibilities. But if Paddy had met with medical misfortune – if he’d had a heart attack or been bitten by a snake or somehow injured – then what had happened to Kellie? Surely the dog would have barked or come home. And the searchers would have found his body. As the days ticked by, it became clear that something more sinister must have occurred. Soon, the search became a murder investigation, as detectives confirmed they believed Paddy had met with foul play.

Officers interviewed the town’s 11 remaining residents. So did we, when we turned up three months after Paddy was last seen. Most people told us he was a larrikin. A great storyteller, they’d said. A bit of a scallywag.

But for every dozen people we spoke to who loved the guy, we’d find one who had a grievance.

Do police have a suspect in the Larrimah case?

Up the road from the Larrimah Hotel, Fran’s Devonshire Teahouse was surrounded by an overkill of peculiar signs. When we first visited in 2018, a short, plump woman met us at the gate and invited us into a lush garden filled with strange collections of stuffed toys.

Fran Hodgetts was then 75 years old and had lived in Larrimah for more than 30 years. As she’d dashed between the kitchen and shaded patio, ferrying cups of tea and scones and cakes, she told us about her life cooking for the grey nomads and truckies. “I was the first in the Northern Territory to make camel, buffalo and crocodile pies,” she said, before revealing her signature pastry’s days on her menu were numbered. “After I sell what I’ve got now I won’t be doing pies and pastry, I’ll be doing waffle pies.”

She told us, in great detail, what goes into a camel-mince waffle pie – it would come with mashed potato and cheese, she said, and would be served crispy.

An entrepreneurial mindset is necessary in the bush – it’s hard to make a living out here. The landscape is hot and brutal, and the tourism season is short. For Fran, it had been even harder. She told us that her nearest neighbour – whose house was on the opposite side of the highway – had been tormenting her for 10 years, throwing roadkill over her fence and poisoning her plants. But life had been even harder still since that neighbour, Paddy Moriarty, went missing – his presence replaced with an enormous missing persons sign.

As details of their conflict had become public, some people had started to point the finger at Fran and her live-in gardener, Owen Laurie. “People are driving past saying ‘murderer, murderer, murderer’,” she’d told us. “It’s terrible.”

Officers questioned them dozens of times, she said. They searched her house and gardens, pumped out her sewerage system. But there was no evidence to connect them to whatever happened to Paddy. And the closer police looked into the case, the more problems they found in Larrimah.

How many people have left Larrimah?

Larrimah has an interesting military history. During World War II it was a remote staging camp for thousands of American and Australian soldiers. But, more recently, the town had been caught in another kind of war.

It was a battle that proved hard to get to the bottom of – the nature of the combat was, like almost everything in Larrimah, unlikely. There was once a town progress association with a thriving community garden, a suite of historical projects and a Tidy Town award under its belt. But somewhere along the way, it got derailed by a raft of allegations: about the murder of a pet buffalo (that may or may not have been baked into pies), the mysterious disappearance of a $17,000 train and the covert installation of some speedbumps on one of the only streets.

Eventually, the town split in two: a pair of competing progress associations for what was then about 20 people. Neither succeeded in progressing the town. Instead, people began moving away. Those who remained still held grudges. One resident was banned from the pub because of an allegation he stole Mars bars. There were lingering accusations of mail theft, bird poaching, arson and illegal grog running.

And then there were the pie wars. Back when there were four businesses in town, selling pies became a competitive sport resulting in backstabbing, sabotage and various reports to the health department.

Paddy moved to Larrimah in 2006 and weighed in on the pastry hostility by erecting a sign outside his place stating that the best pies in Larrimah could be found at the pub. He tried to divert anyone who looked like they were thinking about eating at the teahouse over the road from his place.

Sometimes, he’d yell at tourists who tried to park near his house and he often had run-ins with truckies. It was a habit that made him a few enemies.

In fact, the more we looked into Paddy’s past, the more complicated it all became.

What happened to Paddy from Larrimah?

In a way, trying to find out what happened to Paddy was like one great outback round-up: hundreds of phone calls over three years, thousands of kilometres of driving and about a million cups of tea. We tracked down a rodeo clown, an outback barber, the descendent of a bushranger, three blokes called Tony and a diviner who claimed to have followed traces of energy to where Paddy’s body might have been dumped.

The problem with investigating a life like Paddy’s was that it was full of holes and shadows and inconsistencies. He was loved by many, but everywhere he went, trouble seemed to follow. He’d had feuds with other neighbours, in other tiny towns. He’d left another remote Territory pub where he worked as a yardman – the Heartbreak Hotel – under a cloud of controversy. Outlaw towns are shady places: in some towns he lived in, there are rumours of shoot-outs, prostitutes, drug deals and illegitimate children.

Maybe that’s just the nature of things, out in the hot, dusty Never Never. Stories become warped by heat and time and booze. Tall tales are rampant.

For years we drove up and down that long, burning highway to Larrimah, searching for an answer, and every time we returned, the town was a little older and frailer. Residents started to get sick. Some left, or passed away. And while we certainly came closer to some truths about Paddy’s past and the circumstances of his disappearance, a bigger picture began to emerge. Larrimah was not the only ghost-town in the making – although it was closer to the brink of death than most.

The entire outback is struggling to survive. There are moments of hope, of course – new industries, tourism ventures – but after all we’ve seen, we can’t help wondering how long these tiny, far-flung places can struggle on against progress, the elements and the ways the world is changing. We wonder whether maybe the real outback is also an endangered species.

In part, it’s the infinite possibilities – all strange – that have kept so many people invested in the story of Paddy Moriarty’s disappearance. It’s almost like the landscape conspired to hide the answers. The bush is full of scavenger animals: pigs, buffalo, birds of prey. A body would disappear quickly, out here. It’s like trying to find a needle in the world’s biggest haystack. And by the time Paddy had been reported missing, therehad been several wet season downpours, enough to wash any evidence away.

A two-day inquest in 2018 examined all the brutal possibilities. Although the coroner is yet to hand down his findings, one thing was clear: the man at the centre of the mystery is no longer alive. He hasn’t accessed his bank accounts. He hasn’t left the country. He’s been a fixture of media reports for years, but there have been no confirmed sightings of him. It’s possible he met with an accident – a snake bite, a heart attack, it’s even possible he fell into a sinkhole. It’s a sinister landscape. But the chances of the same misfortune befalling a man and his dog, simultaneously, are slim, if not impossible. More likely, someone has killed them both, and the landscape has swallowed the evidence.